Modern Bodies is the title of the exhibition arranged at the Accademia Galleries in Venice which you should not miss. Until July 27th, 2025 you will have the opportunity to view wonderful art works and artifacts coming from different museums and private collections, all related to the conception of modernity of the human body developed in Venice in the Renaissance. Curated by Guido Beltramini, Francesca Borgo and Giulio Manieri Elia, the exhibition rotates around 89 pieces to talk about anatomy, desire and body manipulation.

You can admire and compare works by Leonardo da Vinci (rarely on show) and Albrecht Dürer, paintings by Giorgione and Vittore Carpaccio, sketches by Michelangelo and Piero della Francesca, just to mention some.

However, should you not be able to plan a visit to Venice in these few weeks left, here are some notes about the art works which will not leave Venice. So no worry, you will still enjoy the revolution the exhibition talks about.

Modern Bodies and the new anatomy studies in the Renaissance

In the early 16th century in Venice a modern approach was applied to the human body. Science with its empirical approach brought intellectuals, physicians and artists to analyze the human body. No more an abstract approach, but a constant research regarding the human body’s diversity and variety.

Measuring became a must, getting your curiosity beyond the surface of the skin. Unveiling with mathematical instruments.

Padua with its university and Venice as a publishing capital city joined their forces: the body would be explored inside, the physician dissecting the corpses would get off the cathedra and soak his hands in the real flesh. No idealization. Books written by physicians were then printed in Venice and would then travel all over and would spread this brand new approach.

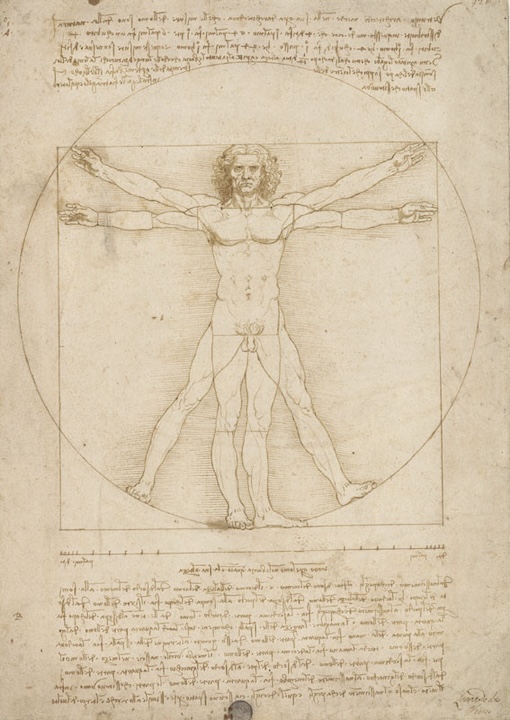

Even the super famous drawing by Leonardo Da Vinci, the so-called Vitruvian Man, was likely meant for a publication —which is the reason why this sheet does not feature hand-written notes Leonardo usually added to his drawings. The sheet seem to date back to 1490-1497 and it is preserved at the Accademia Galleries —now, after 6 years, it is exhibited to regular visitors.

Leonardo Da Vinci, Study of the proportions of the human body, known as the Vitruvian Man, Venice Accademia Galleries, catalogue: 228

Unlike what one generally thinks, Leonardo was not trying to idealize the man’s body. On the contrary he concentrated on the body’s variations related to age, gender and movement: in this work we can’t find a canon, but an attempt to find a summa of the particular versus the ideal.

Desire in Renaissance art

For the first time this approach brought artists in Venice to explore another aspect of the human body: its enigmatic nature, especially when related to desire. Unveiling the body in other words highlighted its mystery and high complexity.

The sleeping beauty in Venetian Renaissance Art

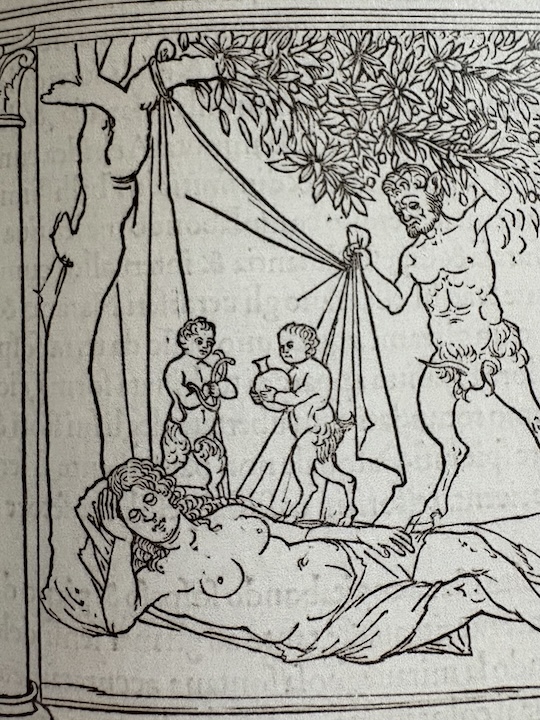

A great example in this sense is the genre of sleeping beauties, another revolutionary contribution Venetian painters brought to art history, likely inspired by that wonderful book by Francesco Colonna, entitled Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, printed by Aldus Manutius in 1499.

Sleeping nymph unveiled by a satyr from Francesco Colonna, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Venice, published by Aldus Manutius in 1499, Giorgio Cini Foundation; detail.

A triangular relationship comes at play while a naked woman keeps her eyes closed while lying amidst a natural landscape while the artist and we, the viewers, look at her, knowing she cannot see us. How does it feel to gain sexual pleasure from watching these sleeping, naked women? They lie offering themselves to us, we are turned into voyeurs, unwillingly. A harmless situation, a moment of suspension as in the end we would like to keep that tension high. If she woke up or, worse, if we woke her up, we all would lose.

Giorgione’s Tempest at the Accademia Galleries in Venice

Even when she is not sleeping, there is a need for distance. Take the famous icon of the Accademia Galleries, Giorgione’s Tempest.

Giorgione da Castelfranco, The Tempest, Venice Accademia Galleries, cat. 915, Provenance: Purchased from Prince Giovanelli, 1932

The lady has certainly chosen the wrong place to sit naked and feed a baby. Is the man on the right protecting her? And why is it that Giorgione had originally painted a lady there and not a standing man (as x-ray analyses showed some years ago)? Not to mention the wrong moment, as the electric lightning and the dark sky tells us there is a storm approaching. At least she should look for some shelter. But no, she is far from the safe city, and that river in between won’t help.

The Ara Grimani from the National Archeological Museum of Venice

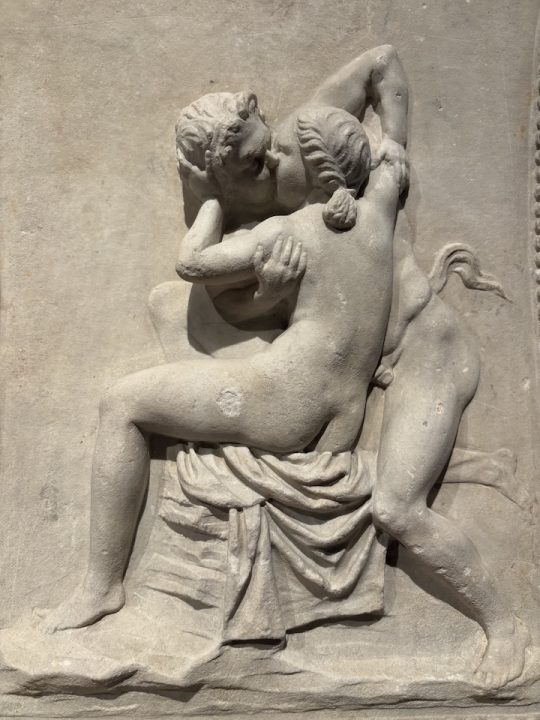

Inspiration for such compositions would also come from the ancient past. Titian certainly loved the Ara Grimani now kept at the Venice Archeological museum in St Mark’s square. The work is a masterpiece of the 1st century BC and it was part of the collection Giovanni Grimani donated to the Venetian State in 1586.

One of the sides of the ara shows a kiss between a satyr and a maenad in the world of Dionysius feasts.

Side to the Ara Grimani, end of 1st century BC, National Archeological Museum in Venice, Collection Grimani

The torsion of her body drives our attention to the buttocks of the maenad and it is impressive to see how Venus holding Adonis by Titian is repeating the motif. Indeed, his brush strokes have highlighted a kind of softness and fleshy character so much that it is difficult to move your eyes away. Difficult to call it “a detail”.

Giorgione’s The Old Lady: the artificial construction

Finally the exhibition focuses on how the human body in the Renaissance is an artificial construction. Fashion, make-up, chopines and dresses —spectacular is the manuscript of the tailor kept at the Querini Stampalia Foundation, dating back to 1540-1570 by Ioanne Jacomo del Conte. But also, you will find incredibly refined protheses for the ones who had lost arms and legs or noses, resembling real limbs.

The exhibition at the Accademia Galleries ends with another masterpiece of the permanent collection: the “Vecchia”, the “Old Lady” by Giorgione from Castelfranco, part of Gabriele Vendramin collection.

Giorgione da Castelfranco, The Old Woman, Venice Accademia Galleries, cat. 272, Provenance: Venice, Manfrin coll., purchased 1856

Aging, the fear of losing youth and mental health, the sense of decay is quite clear in this “portrait” —but is it really a portrait? We are left however with the question of what this painting not just represents, but also with the question of what it was for.

Close by you can find a painting from Budapest, representing a young man.

Art historians mostly agree the two paintings were originally together, meant the one to cover the other one, as in a slide show with an alienating effect. Is the old woman the cover or is it the man’s portrait which covered the lady’s? Fade-in and fade-out: the con-fusion of these two watching us leaves us with a sense of fragility and uncertainty, indeed quite modern.

The Old Woman and the Young Man together, Modern Bodies, Exhibition at the Accademia Galleries, Venice, 2025

by Luisella Romeo

registered tourist guide in Venice, Italy

www.seevenice.it