This is a story woven across Venice, Constantinople and later on Istanbul. It talks about their reciprocal love for gems, enamels and gold. An entangled, at times legendary story between two cosmopolitan cities. A thread across 500 years, a story which shines in all possible directions.

A golden altar screen for St Mark’s Basilica: the Pala d’oro

At the beginning of the 12th century Venice acquired an imposing goldsmiths’ masterpiece from Constantinople, now known as the “pala d’oro”, the golden altar screen. Commissioned by Doge Ordelaffio Falier, the piece was deemed to be perfect for the most important church in Venice, the Doge’s private chapel, St Mark’s.

When you visit St Mark’s basilica, do not miss walking up the few steps leading you to the main altar. Right behind the sarcophagus preserving St Mark’s holy relics, you can admire the “pala d’oro” in all its majesty: 1,927 precious and semi-precious stones — including 320 emeralds, 255 sapphires, 75 rubies — and 526 pearls encrusted on pure gold. Not just. The variety of the color palette increases when you add the over 250 enamels.

Gems and gold from Constantinople to Venice for holy art

The original piece was designed by byzantine goldsmiths. And it could not be otherwise. Literally enamored with the elegance, refinement and historical heritage of Byzantium, Venetians chose the best goldsmiths for their patron.

However, this is for sure the most important jewel ever produced by Venetian civilization, too. As a matter of fact, it was modified by Venetian goldsmiths at least three times across two hundred years. For one good reason: the increasing power of the Venetian State.

Private and individual show off of wealth was deeply criticized in Venice. The State promoted several laws with the purpose of restraining luxury. But public and religious art had to be supported. At all means. At all costs.

Gems and gold to upgrade the “pala d’oro” in St Mark’s church

While modifying St Mark’s golden altar piece, it looks Venetians enhanced contrasts and multicolored effects —almost as if this had more value than the single precious stones. Also, in order to make everyone perceive its preciousness, the golden altar screen was shown in rare occasions.

Christ Pantocrator and apostles of the “Pala d’oro”, the golden altar screen, St Mark’s Basilica, Venice

There’s more. Gems, enamels and gold plaques were added to the original golden altar piece. The upper part of the altar piece was also completely added. In fact, it is supposed to have been sacked in Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade —you can call this a true upcycling process!

Also the image of the Doge Ordelaffio Falier featuring near the plaque of the Virgin Mary is an altered piece. Originally no doge image was displayed. Eventually in 1342-45, the goldsmith Bonensegna erased the original face of the Byzantine emperor to place the face of the Doge of Venice instead.

Detail of the face of Doge Ordelaffio Falier, “pala d’oro”, the golden altar screen, St Mark’s Basilica, Venice

The final result is quite a hybrid piece. Venetians learned how to make enamels or work with filigree and encrust gems, engrave gold and silver, but they never reached the quality of the Byzantine goldsmiths. That’s what makes the pala d’oro unique: its pastiche nature, mixing high quality byzantine heritage with some immature expertise serving Venetian political propaganda.

A crown for the Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent

A couple of hundreds years later, the Venetian ability to deal with precious gems and gold jewelry had reached a completely different level of quality.

Goldsmiths in Venice were the excellence. The market had increased. Gems reached Venice easily: Istanbul, Aleppo, Alexandria were ports you could buy gems traveling from India through Hormuz and Baghdad. Also, the protestant reform with its iconoclastic approach had facilitated the circulation of precious stones. Not to mention the discovery of America had increased the variety of the gems reaching Europe.

But would you imagine that one of these Venetian goldsmiths would sell a crown to the Ottoman Sultan?

The story was believed to be a legend until the 20th century when the name of this goldsmith was discovered together with documents proving the story is to be taken for real.

Luigi Caorlini and the crown for Suleyman

Luigi Caorlini —this was his name— thought of creating a special crown for Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent. A gorgeous helmet in gold, covered with jewels and feathers.

Marin Sanudo saw it in Caorlini’s jewelry workshop in Rialto and described it in detail in his well known diaries:

It was a gorgeous gold helmet covered with jewels, made by the Caorlini. It has four crowns set with very expensive jewels and a finely wrought gold aigrette on which are set four rubies, four large beautiful diamonds worth 10,000 ducats, large pearls weighing twelve carats apiece, a long and beautiful emerald weighing [intentionally left blank] carats, and large and very lovely turquoise. All these are jewels of great worth

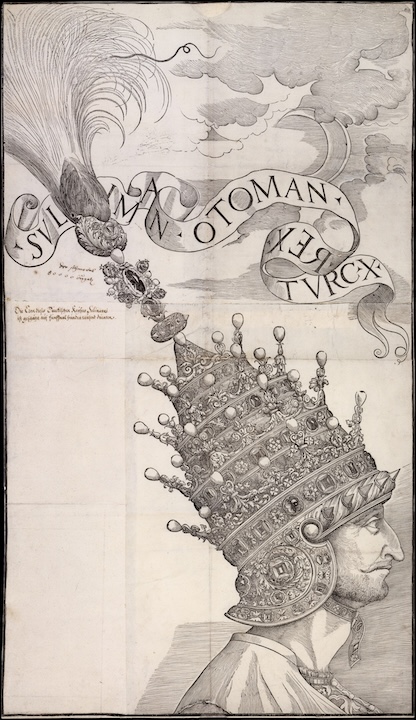

Titian portrayed the sultan wearing this crown and Giovanni Britto made this gorgeous and imposing woodcut kept now at the MET in New New York ( see note at https://archivi.cini.it/storiaarte/detail/14072/stampa-14072.html):

Portrait of Sultan Suleyman, Drawings and Prints (Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1942); http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/338723

The crown is the real protagonist of this art work, don’t you agree? Are you also thinking how much it would cost? Did the Sultan pay for it?

Sultans, Emperors, the Doges and a goldsmith

Caorlini placed it in the Doge’s palace for three days so that everyone could see it. It was then sent to Edirne and then with the help of the Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha it was sold to the Ottoman Sultan. The box it was kept in was in ebony and it was all covered in velvet. Box and crown were valued 144,400 ducats. In the end, there was a small discount and 116,000 ducats were paid instead.

Not bad. That amount compared to half of the Venetian export volume per year. Somehow, the line in German on the woodcut actually mentions more and it would be interesting to understand why such a difference…:

Die Kron dieses Turckischest Keysers Solimanni / ist geschätzt auf fünfmal hundert tausend ducaten (The crown of the Turkish Emperor Soleyman is valued 500,000 ducats)

However, what made that crown so peculiar is not just its cost, but its symbolic meaning, too. The crown is in fact composed of four crowns, representing the Sultan’s dominions in Asia, Greece, Turkey and Egypt.

However, the crown was never really worn. Sultans carried turbans as it shows in the portrait Titian made of the sultan, whose copy is now kept in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna:

Portrait of Sultan Suleyman, copy of a painting by Titian, Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Inv.-Nr. 24291

So why such a deal?

You don’t need to wear a crown to look powerful. The crown featured at a triumphal parade held from Istanbul all the way to Belgrade, which impressed everyone in the western world. It was meant to be a political response. Two years before, in fact, the Pope had crowned the Sacred Roman Emperor Charles V with a similar crown —featuring three crowns only, though. French King Francis I had not been happy and in 1536 he decided to ally with Soleyman against Charles V.

It is then clear that it was thanks to this amazing jewel that Venetians took a very precise political position: supporting the power of the Sultan (and indirectly the French king) versus the Pope. What I like best is that a Venetian goldsmith managed to get very well paid for his work, too.

by Luisella Romeo

registered tourist guide in Venice, Italy

www.seevenice.it